|

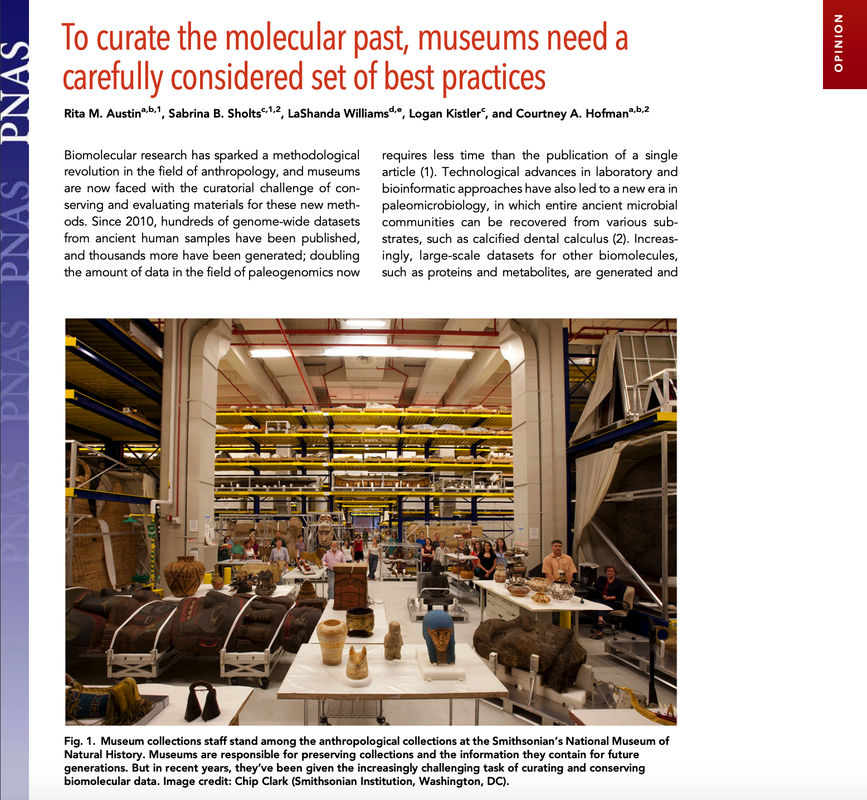

This opinion piece is a timely and critical perspective on the role of museums in preserving their specimens in the multi-omics era. Here, LaShanda and the other authors provide new guidelines currently implemented at the Smithsonian to protect the rich biomolecular resources maintained in museum collections worldwide. Read more here.

It all started with a happy accident. When cleaning out a basement lab at Hutcheson Memorial Forest (HMF), the Lockwood Lab discovered several boxes of old bird banding records. These records provided an in depth look at what birds were present in the forest during the 1960s and 1970s.

With this information in hand, the Lockwood Lab re-established the bird banding efforts to investigate how the modern bird community compared with the historic records. Starting in 2009, members of the Lockwood Lab spent their summer weekends inside Hutcheson Memorial Forest setting out mist nets to capture and band birds. This banding effort continued until 2015 at which point Jeff Brown begun comparing the bird communities from the two time periods. Analysis confirmed what many visitors to the forest anecdotally knew. Birds were missing. Many species that were once common such as ovenbirds (Seiurus aurocapilla) and american redstarts (Setophaga ruticlla) were no longer present. However, other species such as the common yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas) have hairy woodpeckers (Leuconotopicus villosus) are more common than they previously were. To better understand why species were disappearing, Brown and his collaborators looked to the life history of the species within the forest as well as how the forest itself has changed. Many of the species that are no longer present at HMF are migratory and ground nesting species. It is unsurprising migratory species are having a more difficult time establishing in HMF. Regional trends show HMF has become increasingly isolated as the surrounding areas have become more developed. Additionally, within HMF the understory has been taken over by non-native species such as Japanese stilt grass (Microstegium vimineum). The invasion of non-native plant species combined with increased herbivory from white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) create an understory that is inhospitable to many ground nesting species. For a complete version of this story please see the journal article in Biodiversity and Conservation Despite this bleak news, there is hope for the future of HMF. The current state of the forest is largely due to a hands-off management approach that was taken over the last few decades. However, current HMF managers have implemented a more proactive approach by installing a deer fence around the forest. While it is still early in this management process, native plants have started to return, and the first record of an ovenbird was observed in June of 2018. |

We seek to further the social, cultural, academic and research interests of the students in the graduate program in Ecology and Evolution and act as a link between the graduate students and the faculty. Archives

November 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed